Japanese Lesson 3 - A View on WWIII asked one of my colleagues about what the Japanese views of WWII were. He said many Japanese in the generation before him feel envious of the U.S. and perhaps ashamed -- not ashamed of doing anything wrong but about losing. The envy and shame seemed to be accentuated by the fact that it was the U.S. who helped reconstruct Japan after the war.

I asked, "But don't the Japanese feel any guilt for what they did?"

He responded, "The people did not know any better. The blame rests upon Emperor Hirohito and Shintoism (the national religion then). The ignorance of the people was like that of North Korea in our modern times. This is [the history] they taught at my school in Japan."

I wonder did the people know any better? Can it really be blamed on one person? It's like blaming Hitler alone for all of Germany's actions or Mussolini for all of Italy's actions. People do have consciences and people can choose right or wrong. As you may know, there were Germans during WWII who chose to do good when they hid refugees and joined the resistance movement to overthrow the Third Reicht.

Then again, in Japan, the sense of hierarchy and community over individual is so much more ingrained than in the West. And if they were like North Korea, perhaps the soldiers knew only whom they were told was the enemy.

I read another book by Shusaku Endo called

The Sea and Poison. It focused on a hospital in Japan during WWII in which a team of surgeons receive a American POW, experiment on him, and kill him. Knowing what was to come down, right as the experimental operation commenced, one of the residents stepped aside because he realized the immorality of the whole business. Yet he didn't try to stop it; he just stood at a distance in nonparticipation. Another resident looked at him with disdain, thinking, 'You've already gone this far; you are as guilty as all of us.' This is an example of 1940's Japanese with consciences and knowingly choosing against it.

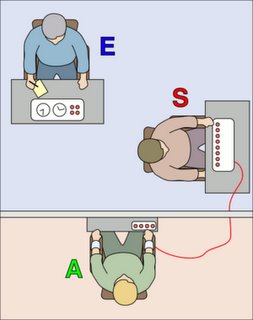

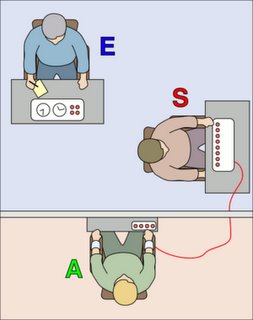

But this is too harsh, too much of a strawman. There is a famous Yale study on people responding to authority. You may know the

Milgram experiment consisting of a researcher (E), a test subject (S) and a voice actor (A). The researcher told test subjects to be teachers prompting an oral exam. The actor played a student responding to the exam questions. If the student answered wrongly, the teachers were told to to press switches that inflicted an electric shock to the student. Each incorrect answer led to a stepwise increase in electric shock up to a lethal dose. The student would initially act angered, then start screaming, and finally stop responding altogether, as though unconscious or dead.

This study found that 65% of normal adults sampled punished the students to the maximum lethal 450 volts when commanded by an authority (the researcher). 0% stopped before 300 volts. This shows how

weak people's minds are -- malleable to people in authority, not just to "group think." But the test subjects still made a choice against their conscience as revealed by their hesitancy and agitation through the process, looking back at the researcher before untimately choosing against good. It also shows how easily people choose evil.

The question then is, what leads people to make the moral choice? What distinguishes those few who resisted Nazi Germany and the few who quit early in the Yale study?